The Crash

On the first trading day of August, the QQQ ETF, which tracks the Nasdaq 100, began the morning putting in a fresh nearly two-week high. The American economy continued to show signs of strength, and the probability of the Federal Reserve cutting rates in the coming weeks was very high, further supporting the narrative of a “soft landing” for the US economy. It was business as usual for this strong bull market. What preceded that fresh high was 14 hours of panic trading and deleveraging, which saw the QQQ drop over -11.3%, illustrated in the chart below.

Source: Factset

Many reasons have been given for this selloff, such as worse-than-expected US unemployment data, a problematic rotation away from large caps, recent weak global demand for equities, and Japan’s new central bank interest rate policy. Although all these concerns and realities are valid, they don’t equate to the extreme fear and panic we witness in the market.

Source: Factset

The VIX (Chicago Board of Exchange’s Market Volatility Index) shown above, also known as the fear gauge, spiked nearly 400% over those 14 hours of market trading. Bid (the price buyers are willing to buy at) and Ask (the price sellers are willing to sell at) spreads saw massive widening even for the most highly traded liquid securities. Investors were scrambling to buy protection on their investments in the form of Put Option buying, seemingly with little regard for the price they had to pay for their insurance.

Was this violent selloff a one-off event or the beginning of a much larger correction? The market is where millions of investors make decisions for various reasons. Without a crystal ball, consistently predicting the result of the following few million decisions isn’t possible. Instead, we must step back and assign educated probabilities to what may happen moving forward using the available information and knowledge.

The chart below shows the QQQ ETF for the last year. As you can see, it has not broken its upward market trendline. When it opened down -5% on August 5th, right on its weekly trendline, many began buying. The volume bars at the bottom of the chart also show that the number of trades that caused this pullback in these stocks was below average. In technical analysis, volume is often a very good indicator of the strength and validity of a price move.

Source: Factset

For the first half of the 20th century, August was the best-performing month for stocks due to agricultural harvesting. Now that less than 2% of North Americans farm, it has become the second worst month of the year for the Nasdaq 100 and S&P 500 over the last 50 years. September is the worst month historically. So, there is a market-wide expectation for volatility in August and September, and given that this is starting in August, we should expect to see a lot more volatility, as volatility does tend to lead to more volatility. However, the upcoming tailwinds for the market still look to be much stronger than the headwinds. As long-term investors, we should welcome volatility, which often leads to great opportunities. Fun fact: in an election year, the return for the last seven months of the year has been negative only twice during the previous 80 years.

The Scary July US Jobs Report

One of the major fears that helped send markets lower recently is that the health of the US economy is worse than perceived. The primary data points that fueled this notion at the end of July were the US non-farm payroll numbers, 114k vs. the 185k consensus estimates, and the employment rate increasing to 4.3% vs. the 4.1% estimate. Based on these two numbers, a reasonable conclusion would be that the US economy may be normalizing from its previously robust state. The more pessimistic fear, recently observed in financial markets, is that these stats are a significant threat that a weak labour market could cool the economy into a recession.

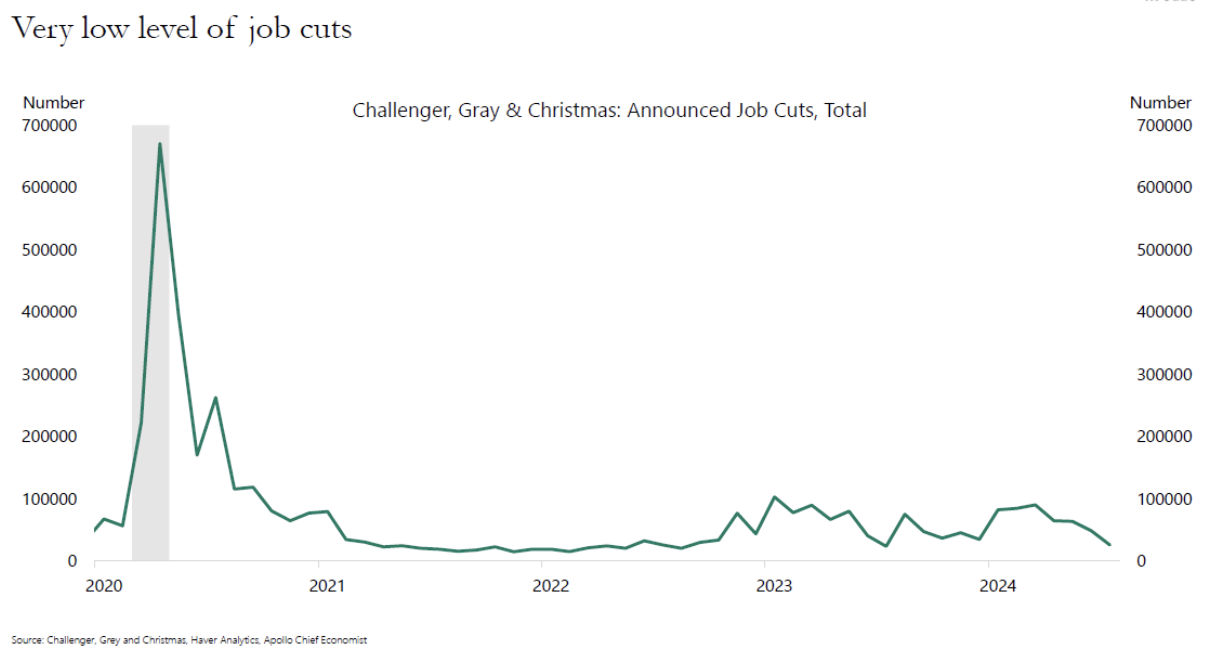

The reality is that these are just two data points, which is never enough to draw any conclusions about economies. Torsten Slok, Chief Economist at Apollo Group, suggests and illustrates in the chart below that job cuts aren’t rising and that higher employment is most likely the result of increased labour supply due to immigration.

That doesn’t quite explain the low nonfarm payroll numbers, but if the labour market were genuinely softening, that would directly result from a weakening economy. However, other economic indicators point to just the opposite.

Both corporate and consumer default rates are declining. Announced planned job cuts are declining. The JOLTS job reports confirm that the number of jobs available isn’t decreasing. More recent short-term daily and weekly indicators also support the narrative of a strong US economy. OpenTable, the restaurant booking software, releases weekly data on the number of reservations made; these numbers are not declining. The US TSA tracks the number of times people have their passports checked daily, indicating the amount of money spent on travel; it has not changed recently. Weekly same-store retail sales and hotel demand show no signs of a decline. Loan growth from banks has been increasing over the last two months; if the economy were in trouble, credit growth would be falling, not rising. Weekly bankruptcy filings are falling. Credit card spending is not slowing, and more importantly, the ratio of money spent on consumer discretionary relative to consumer staples goods isn’t changing. Broadway and movie attendants remain constant.

There is not enough discouraging data to support any reasonable concern over the health of the US economy at this time, but that may change in the future. There are certainly cohorts of the US economy doing much worse than others. Credit Card delinquencies for people in their 20s are very high, as are auto loan delinquencies for Americans in their 20s and 30s, currently at a level not seen since 2008 when unemployment was at 10%. If unemployment takes a turn for the worse, it will hit this portion of the economy the hardest and could have significant ripple effects throughout the US economy.

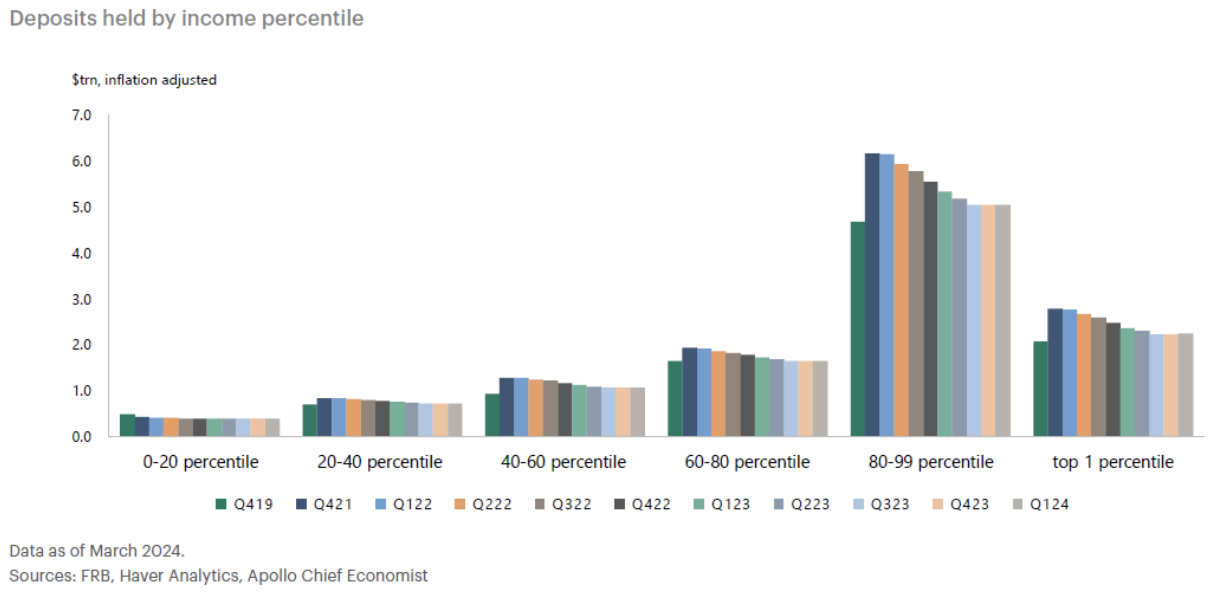

People in the bottom quintile of income distribution must rely much more on their next pay cheque to survive now more than ever, as the effects of high interest rates have taken away their savings. This is almost in complete contrast to the other 80% of Americans who still have more savings today than they did in 2019.

This is one major reason why the transmission effect of the Fed’s policy rates on the economy has been so muted. A small portion feels the negative effects of higher rates, while a much more significant portion benefits from them. This is most evident in US auto sales, which are heavily reliant on consumer financing and have increased since the Fed started raising rates two years ago.

One month’s worth of data doesn’t change much for economists and the Federal Reserve; it is trends they are rightfully interested in, and the US economy is still trending upward.

The Unwind of the Japanese Carry Trade

The most plausible technical reason for this month’s sell-off in global equities is the beginning of an unwind of a very popular investment strategy, the Japanese Carry Trade. The basis of a carry trade is to borrow money in one country for a relatively low interest rate and invest that money in another country to earn a higher rate of return. Given its long-standing zero interest rate policy, the Bank of Japan has made this a very lucrative trade. A typical execution of this trade would be to borrow X amount of Yen (the Japanese currency) at almost no cost and convert it into USD to buy US Treasury Bonds, paying you an interest of 4%. In this example, the trade generated a net 4% return using someone else’s money. The risk of this trade is that the yen you borrowed will appreciate against the USD, and the amount you must pay back will be more than the amount you borrowed in USD terms. To shift this risk to someone else, it is not unusual to add a currency hedge to the position, but given how profitable shorting the yen has been, it is probably not part of many managers’ trade plans. A popular carry trade is to borrow from Japan and buy US equities, like the “Mag 7”. This is a very cheap way to add leverage to a long equity position, and what many large traders and hedge funds have done.

On July 11th, the Yen was hovering at a four-year low against the USD as demand for cheap financing from Japan seemingly peaked. Since then, many Japanese politicians have complained about the economic dangers of extreme currency depreciation. They have strongly suggested that the Bank of Japan and the Ministry of Finance focus their policies on restoring its value. Financial markets seemed to agree with the logic behind these demands and began to price in a high likelihood that the BOJ would raise rates soon. The Yen began to rise as traders began selling their securities, selling the currency those securities were held in, and buying back Yen to repay the borrowed money. On July 31st, the Bank of Japan increased its overnight rate to 0.25%, ending its long-standing zero-interest rate policy. From the July 11 lows to the recent Aug 5th highs, the Yen appreciated 13.83% against the USD, a remarkably quick move for the foreign exchange rate of two developed countries.

Source: Factset

“It’s effectively a big deleveraging event caused by the short squeeze in the yen,” said Kyle Rodda, a senior market analyst at Capital.Com. “It’s forcing widespread liquidation across markets.” The segment of the market that is exposed to this market event and the ripple effects it may cause are still unknown. There are some signs that the worst of it is over, such as the extreme spike in the VIX during this sell-off, and the fact that it has subsided to normal levels relatively quickly is certainly a positive sign, suggesting that fewer are concerned about its systemic effects moving forward. The VIX and the USD/JPY will be key indicators to watch.